Dr. Ambedkar and Columbia University: A Legacy to Celebrate

Every morning, I look forward to glancing at Dr. Ambedkar’s bust, in the far East corner of the Lehman Social Sciences Library, on my way to work. My eyes first rest on the bright garlands (offerings of admirers) that often adorn the bust, hanging around the neck, and then, unfailingly, go to the glasses carved in dark bronze (like the rest of the sculpture), almost indistinguishable from the broad face, but yet magnetically pulling my eyes in. I find myself drawn into the eyes of the “Father of the Constitution”, the “Doctor and Saint” or as people affectionately refer to him, Baba Saheb Ambedkar (1891-1956), and I unfailingly detect a subtle smile. I tried looking at the glasses, and the eyes, from different angles, and the smile is always there, barely perceptible, but definitely present. There is something slightly jolting, refreshing about this daily ritual: looking for that subtle grin has come to frame my mornings, and in fact, my whole experience of my working space, the Lehman Social Sciences Library. A grand library, designed like a “ship of state”, and part of the SIPA and Law School complex (–both designed by Max Abramovitz and Wallace Harrison— the latter is known for leading an international team of architects on the design of the United Nations Headquarters in NYC, and the former for designing the Philharmonic Hall at Lincoln Center –) the Lehman Social Sciences Library opened in the early 70s, and is often jokingly referred to by students as “the NASA Headquarters” or even “the bunker from the cold war”, for its subterranean open aesthetics and its typical late 60s, early 70s look. That is very far from how I experience this space, and I just realized recently, it is in large part due to my daily anticipation of seeing that fleeting grin in the morning subterranean light of Lehman Library’s open skyline.

Every morning, I look forward to glancing at Dr. Ambedkar’s bust, in the far East corner of the Lehman Social Sciences Library, on my way to work. My eyes first rest on the bright garlands (offerings of admirers) that often adorn the bust, hanging around the neck, and then, unfailingly, go to the glasses carved in dark bronze (like the rest of the sculpture), almost indistinguishable from the broad face, but yet magnetically pulling my eyes in. I find myself drawn into the eyes of the “Father of the Constitution”, the “Doctor and Saint” or as people affectionately refer to him, Baba Saheb Ambedkar (1891-1956), and I unfailingly detect a subtle smile. I tried looking at the glasses, and the eyes, from different angles, and the smile is always there, barely perceptible, but definitely present. There is something slightly jolting, refreshing about this daily ritual: looking for that subtle grin has come to frame my mornings, and in fact, my whole experience of my working space, the Lehman Social Sciences Library. A grand library, designed like a “ship of state”, and part of the SIPA and Law School complex (–both designed by Max Abramovitz and Wallace Harrison— the latter is known for leading an international team of architects on the design of the United Nations Headquarters in NYC, and the former for designing the Philharmonic Hall at Lincoln Center –) the Lehman Social Sciences Library opened in the early 70s, and is often jokingly referred to by students as “the NASA Headquarters” or even “the bunker from the cold war”, for its subterranean open aesthetics and its typical late 60s, early 70s look. That is very far from how I experience this space, and I just realized recently, it is in large part due to my daily anticipation of seeing that fleeting grin in the morning subterranean light of Lehman Library’s open skyline.

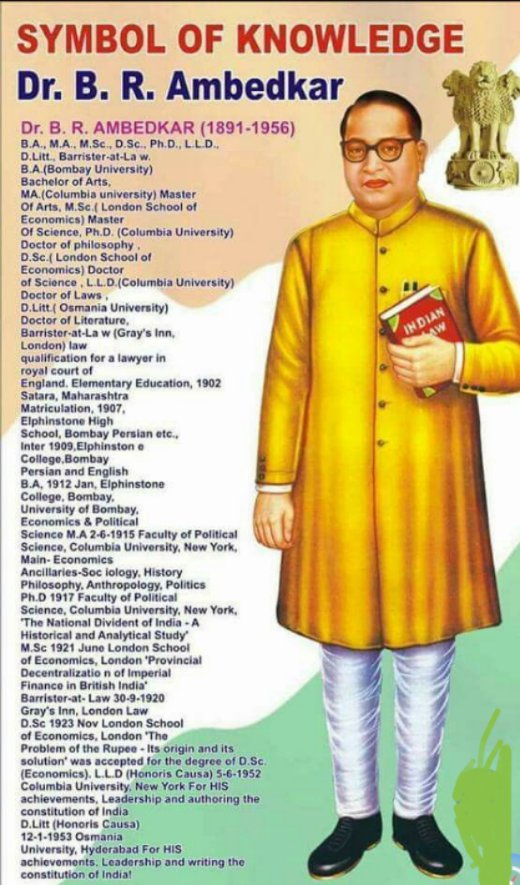

For those of you who may not know, Dr. Ambedkar is a Dalit, an Indian jurist, economist, politician, activist and social reformer, who systematically campaigned against social discrimination towards women, workers, but most notably, towards the Dalits, and forcefully argued against the caste system in Hindu society. Dr. Ambedkar was the main architect of the Constitution of India, and served as the first law and justice minister of the Republic of India, and is considered by many one of the foremost global critical thinkers of the 20th c., and a founder of the Dalit Buddhist movement. Ambedkar’s fight for social justice for Dalits, as well as women, and workers consumed his life’s activities: in 1950 he resigned from his position as the country’s first minister of law when Nehru’s cabinet refused to pass the Women’s Rights Bill. His feud with Mahatma Gandhi over Dalit political representation and suffrage in the newly independent State of India is by now famous, or I should say notorious, and it is Dr. Ambedkar who comes out on the right side of history.

The bronze bust, sculpted by Vinay Brahmesh Wagh of Bombay, was presented by the Federation of Ambedkarite and Buddhist Organizations, UK to the Southern Asian Institute of Columbia University on October 24, 1991, and then the marble pedestal on which the statue now rests was donated by the Society of the Ambedkarites of New York and New Jersey, and placed in Lehman Library in 1995. The bust is the only site in the city where Dr. Ambedkar is honored, and is one of the most popular sites in enclosed spaces on campus that I have seen (you have to walk past the library entrance to get to it).

Every year, on April 14 th, Ambedkar’s birthday, Ambedkar Jayanti or Bhim Jayanti, is celebrated in India (as an official holiday since 2015), at the UN (since 2016), and around the world. On this day, many visitors flock to Lehman Library, to pay tribute to Baba Saheb and place garlands on the bust. The sight of the visitors– many of whom come to Columbia just to see the bust and pay homage to the man who changed Indian society, brings home the significance of recognizing our critical thinkers, across cultures, eras, languages, divisions and types of social injustice, in the public fora of libraries. It is a powerful reminder that it is through scholarship and indeed through libraries and learning that human differences and injustices can be better understood, addressed and perhaps overcome.

I knew about Dr. Ambedkar’s  many achievements even before I got to Columbia. But what I did not know was Dr. Ambedkar’s deep connection to the University. After struggling to overcome prejudice as a Dalit, and gain an education, Ambedkar passed the BA examination at the University of Bombay in 1912, and took a short lived administrative position before venturing to New York on a scholarship. He joined Columbia University at the age of 22, and it is here that much of his political thought took form, mostly, as many argue, under the influence of John Dewey.

many achievements even before I got to Columbia. But what I did not know was Dr. Ambedkar’s deep connection to the University. After struggling to overcome prejudice as a Dalit, and gain an education, Ambedkar passed the BA examination at the University of Bombay in 1912, and took a short lived administrative position before venturing to New York on a scholarship. He joined Columbia University at the age of 22, and it is here that much of his political thought took form, mostly, as many argue, under the influence of John Dewey.

Years later, Dr. Ambedkar writes: ‘The best friends I have had in life were some of my classmates at Columbia and my great professors, John Dewey, James Shotwell, Edwin Seligman, and James Harvey Robinson.’” (Source: “‘Untouchables’ Represented by Ambedkar, ’15AM, ’28PhD,” Columbia Alumni News, Dec. 19, 1930, page 12.)

Ambedkar majored in Economics, and took many courses in sociology, history, philosophy, as well as anthropology. In 1915, he submitted an MA thesis entitled: Ancient Indian Commerce. In 1917, he went on to write a second M.A. thesis entitled: “National Dividend of India–A Historic and Analytical Study”, which would go on to form the nucleus of his Ph. D. thesis. About the second MA thesis, Ambedkar writes to his mentor Prof. Seligman, with whom he forged a long and friendly correspondence, even after he left Columbia: “My dear Prof. Seligman, Having lost my manuscript of the original thesis when the steamer was torpedoed on my way back to India in 1917 I have written out a new thesis… […from the letter of Feb. 16, 1922, Seligman papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University” cited in Dr. Frances Pritchard’s excellent online website about Ambedkar]. In 1920, Ambedkar writes: “My dear Prof. Seligman, You will probably be surprised to see me back in London. I am on my way to New York but I am halting in London for about two years to finish a piece or two of research work which I have undertaken. Of course I long to be with you again for it was when I was thrown into academic life by reason of my being a professor at the Sydenham College of Commerce & Economics in Bombay, that I realized the huge debt of gratitude I owe to the Political Science Faculty of the Columbia University in general and to you in particular.” B. R. Ambedkar, London, 3/8/20” , (Source: letter of August 3, 1920, Seligman papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, cited in Pritchard’s website ).

If it is Seligman he stayed in touch with and corresponded throughout, the person who most influenced his thought and shaped his political, philosophical and ethical outlook, was Dewey. For many thinkers, the links between Dewey and Ambedkar’s ethical and philosophical thinking are obvious. Ambedkar deeply admired Dewey and repeatedly acknowledged his debt to Dewey, calling him “his teacher”. Ambedkar’s thought was deeply etched by John Dewey’s ideas of education as linked to experience, as practical and contextual, and the ideas of freedom and equality as essentially tied with the ideals of justice and of fraternity, a concept he would go on to apply to the Indian context, and to his pointed criticism of the caste system. Echoing many ideas propagated by Dewey, Ambedkar writes in the Annhilation of Caste: “Reason and morality are the two most powerful weapons in the armoury of a reformer. To deprive him of the use of these weapons is to disable him for action. How are you going to break up Caste, if people are not free to consider whether it accords with reason? How are you going to break up Caste, if people are not free to consider whether it accords with morality?”

Having sat in several classes given by Dewey, and as early as 1916, Ambedkar would go on to address, at a Columbia University Seminar taught by the anthropologist Prof. Alexander Goldenweiser (1880-1940), his colleagues and friends with many of the ideas he later developed in his famous book: the Annihilation of Caste. The paper “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis, and Development” contains many similarities to the Annihilation of Caste, and some of the books’ essential tenets., as acknowledged by Ambedkar himself (Preface to the 3rd edition, Annihilation of Caste).

Ambedkar would join the London School of Economics for a few years and submit a thesis there, but then, he would eventually come back to Columbia, to submit a Ph.D. thesis in Economics, in 1925 under the mentorship of his dear friend Prof. Seligman, entitled: The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India. Ambedkar kept his intellectual and spiritual ties with his Alma Mater, even after graduation, and the University also followed his news: In 1930, the Alumni Bulletin reports about Ambedkar addressing a round table in London about the importance of abolishing the caste system in India. In 1952, Dr. Ambedkar received an honorary LLD Doctorate Degree in Law, as part of the University’s Bicentennial Special Convocation. For the occasion, President Kirk described him as “one of India’s leading citizens–a great social reformer and a valiant upholder of human rights.” On his way to receive the honorary degree, Dewey passed away, and Ambedkar wrote to his wife and beloved companion, bemoaning the loss of Dewey, and mentioning how sad he was not to be able to see him.

Ambedkar would join the London School of Economics for a few years and submit a thesis there, but then, he would eventually come back to Columbia, to submit a Ph.D. thesis in Economics, in 1925 under the mentorship of his dear friend Prof. Seligman, entitled: The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India. Ambedkar kept his intellectual and spiritual ties with his Alma Mater, even after graduation, and the University also followed his news: In 1930, the Alumni Bulletin reports about Ambedkar addressing a round table in London about the importance of abolishing the caste system in India. In 1952, Dr. Ambedkar received an honorary LLD Doctorate Degree in Law, as part of the University’s Bicentennial Special Convocation. For the occasion, President Kirk described him as “one of India’s leading citizens–a great social reformer and a valiant upholder of human rights.” On his way to receive the honorary degree, Dewey passed away, and Ambedkar wrote to his wife and beloved companion, bemoaning the loss of Dewey, and mentioning how sad he was not to be able to see him.

The Columbia University Archives and the Columbia University Libraries hold many resources related to Dr. Ambedkar and to the Dalit movement and Dalit literature. For any inquiries regarding relevant resources, please do not hesitate to contact us: Gary Hausman: South and Southeast Asian Librarian, Global Studies; Rare Book and Manuscript Library: RBML Archivists

14 thoughts on “Dr. Ambedkar and Columbia University: A Legacy to Celebrate”